Tags

The writers of Victorian periodicals were enthralled by scholarly oddities. Periodicals published scores of stories portraying real and fictitious historians, antiquaries, and classicists as archetypical eccentrics. The Strand Magazine, for instance, introduced John Stuart Blackie, a classical scholar from Edinburgh, in 1892 by foregrounding his quirky habits. Apparently, Blackie was like a walking and talking encyclopedia who “quote Plato one moment, dilate on the severity of the Scottish Sabbath the next, and with lightning rapidity burst forth into singing an old Scotch ballad that sets one’s heart beating considerably above the regulation rate.” If this was not enough to convince the readers that Blackie was truly an oddball erudite, the reporter explained how he, when “worried for a sentence, or troubled for a rhyme,” walked in circle “humming ‘I am a motive animal’.” An eccentric was one of the most common “types” of scholars which Victorian periodical literature cherished. Some other popular types were the recluse ascetic, effeminate antiquary, combative scientist, and the self-absorbed specialist. There were numerous real-life models to match these types and readers were greatly amused by the peculiarities of the greatest minds of their age.

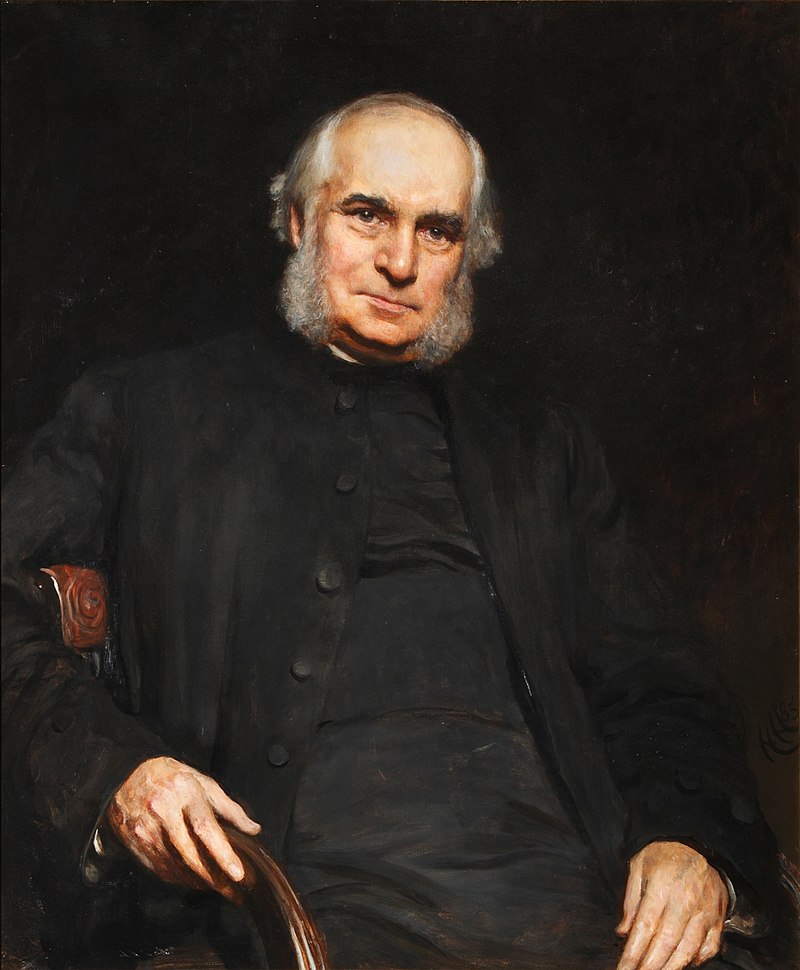

Each of these types would deserve a blog post of its own, but let’s turn our attention to the self-absorbed specialist who was characterized by an overbearing personality, conviction of the superiority of his (rarely hers) mind, and a compulsion to share his views with whomever happened to be around. The egomania made the self-absorbed specialist unbearable company in an age that held such virtues as modesty, altruism, self-restrain and self-discipline in high esteem, and appreciated refined sociability and simplicity of manner. After all, selfishness was considered a serious flaw in the moral character of an educated middle-class man. A manly man was always in charge of his conduct and emotions. Even the slightest hint of contrary alarmed scholars and demanded urgent public image polishing. A good example of this is William Stubbs, Regius Professor of Modern History in Oxford.

Stubbs, as I have written elsewhere, was venerated by his peers as the embodiment of the new scientific history. Nevertheless, and despite his colleagues’ avid hero-worshipping, a persistent rumor about Stubbs as an unbearable erudite circulated among the public. Stubbs, being one of the most eager constructors of his heroic public image, was aware of both the rumor and how stories about his assumed egotism could damage his otherwise untarnished reputation. He was so concerned about the situation that he decided to dedicate part of his last statutory lecture in Oxford in 1884 to correcting such misconceptions about his character.

According to the story which Stubbs wished to refute, his first encounter with the young historian John Richard Green had been strained by his egotistic tendencies. The two had met on a train on their way to visit another well-known historian, Edward Freeman. One of them had been “a stout and pompous professor,” the other “a bright ascetic young divine.” The “burly professor” had “aired his erudition by little history lectures … on every object of interest that was passed on the way.” Stubbs found all this ridiculous and entirely unfounded. His side of the story was that, yes, he and Green had met for the first time on a train on their way to visit Freeman, but that he had certainly not bored Green with arrogant lectures on every possible topic that had occurred to him. On the contrary, the two had immediately fallen into an inspiring conversation and that this vibrant exchange of ideas had continued since then until Green’s premature death in 1883. “And that is all,” Stubbs ensured. The story was nothing but “confusion and inversion.” After his rhetorical attempt to restore his reputation as a modest, selfless, and generous scholar, he reverted to his professorial pose and rounded off the tale by reminding the attendees how history was often “written out” of such unfounded tales.

The stories about scholarly eccentricity flourished in fact and fiction in Victorian Britain. For scholars, the images of dust-covered historians perusing illegible manuscripts or antiquaries tramping across muddy fields in a frantic search for a Roman teapot were insulting and alarming at once. They feared that the constant mockery might undermine both their authority and the credibility of scientific knowledge. Moreover, the parodies of compulsive behavior and egomania threatened the morality and manliness of their character. This was anything but insignificant at a time when behavior and respectability were critical for one’s social stature and membership in the society. Because of this, John Ruskin, an Oxford art historian and an inspiration for countless rumors and pernicious anecdotes, must have been pleased to read how the famous celebrity-journalist Edmund Yates complimented him in The World for never monopolizing the social space. After observing how Ruskin had hosted a party at his home, Yates was able to assure that Ruskin’s guests had no need to “be afraid of being victimised by that spirit of self-conscious dictation … which has been known to spoil enjoyment in the company of some literary men.” This was praise that would have exhilarated any man with scholarly ambitions.

Sources

[Anon.]. “Illustrated Interviews. No. IX. – Professor Blackie.” The Strand Magazine, 1892.

Stubbs, William. Seventeen Lectures on the Study of Medieval and Modern History and Kindred Subjects. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1886.

Yates, Edmund. Celebrities at Home. Printed from ‘The World,’ vol. 2. London: Office of ‘The World’, 1878.